When we booked our trip to Sabah, I knew that there had been a Prisoner of War camp in Sandakan and had heard of the Death Marches but knew very little more. What we learnt on our visit about the enormity of the crimes committed by human beings on fellow humans was hard to comprehend.

Since then my husband has read The Story of Billy Young by Anthony Hill and Sandakan: A Conspiracy of Silence by Lynette Ramsay Silver. I have not attempted either as the thought of revisiting that period of history is just too confronting.

However today is ANZAC Day when we remember those who didn’t make it back home so I thought it was a good opportunity to bite the bullet and try to answer a few questions. Why were the guards so brutal? Were there any survivors? How did so many die? I’m not attempting to read Silver’s outstanding book in one day so am using the ANZAC Portal from the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, specifically Sandakan 1942-45 as my main source.

In 1945 Borneo was still occupied by the Japanese, and at the end of the Pacific war in August, Australian units arrived in the Sandakan area to accept the surrender of the Japanese garrison. Just 16 kilometres out of Sandakan, in a north-westerly direction, was the Sandakan POW Camp. Here, between 1942 and 1945, the Japanese had at different times held over 2700 Australian and British prisoners. The POWs were brought from Singapore to Borneo to construct a military airfield close to the camp. By 15 August 1945, however, there were no POWs left at Sandakan Camp.

So what had happened to 2700 men? For the next two years, between 1945 and 1947 the area from Sandakan to Ranau, 260 kilometres to the west, was searched, and the remains of 2163 Australian and British POWs were uncovered. Hundreds of bodies were found at the burnt-out ruins of the POW camp.

Research has indicated that some 2428 Allied servicemen—1787 Australians and 641 British—held in the Sandakan Camp in January 1945 died between January and August 1945 in Japanese captivity.

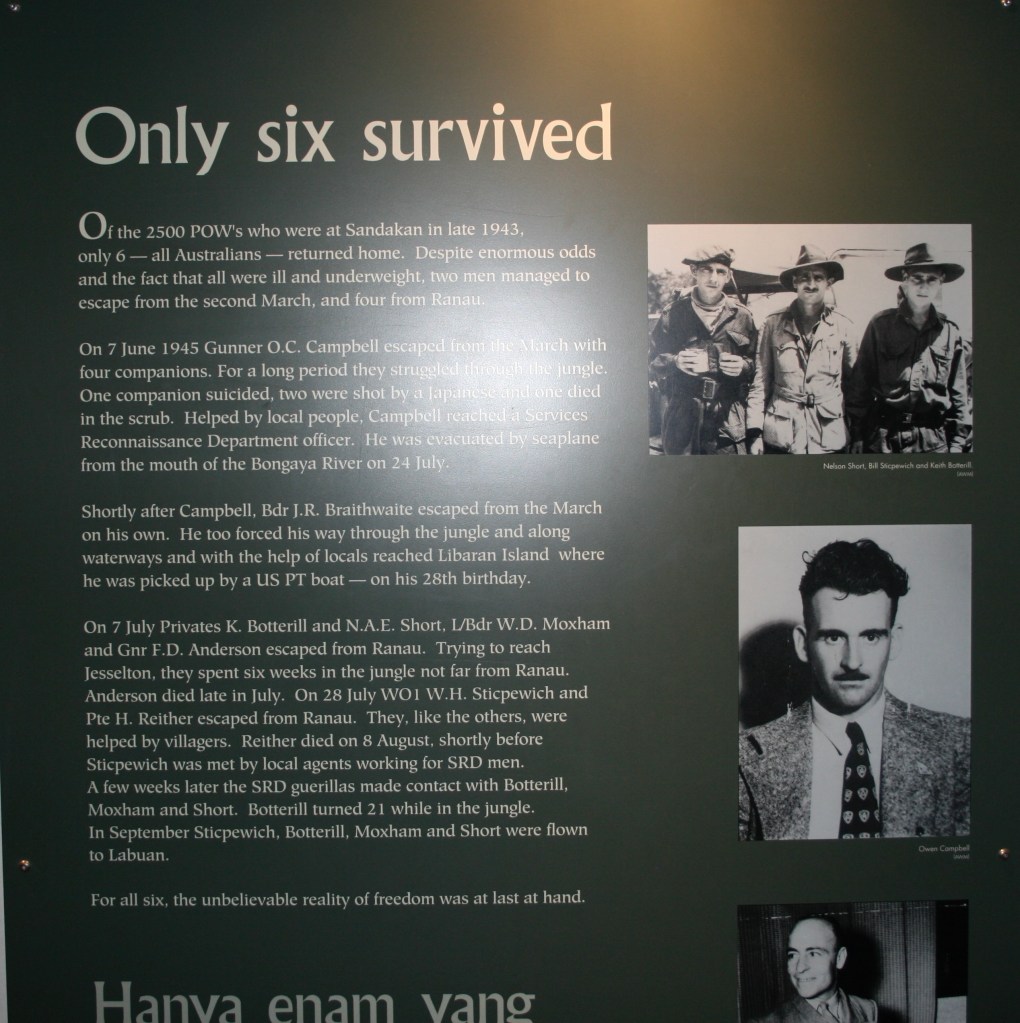

They were so close to being freed as the war was nearly over. How is it that so few (only six) made it home?

Until April 1943 the soldiers were worked hard but had enough to eat and kept their spirits up with concerts. Then the new guards arrived, from Formosa, under Japanese leadership. They were considered the lowest of the low by the Japanese, not even good enough to fight, so brutalised and resentful, they took out their anger on the prisoners. In July an intelligence ring run by some officers with local people was discovered, resulted in severe punishments. There must have been some hope when in September 1944 Allied planes began bombing Sandakan and the airfield. This was seen by the captors as a reason to reduce rations as the prisoners were no longer needed to work on the bombed-out airfield. The plan was made to move the prisoners to Ranau in the mountains where they could be used as supply carriers. The first group of 455 Australians and British set off with only four day’s rations, no boots, in rain, suffering from malnutrition and numerous other illnesses. If they fell they were dragged into the bushes and bayoneted or shot. By June, five months later, there were six left.

Back at the camp in Sandakan, things were no better.

Hundreds of Australian and British POWs between January and August 1945 expired at Sandakan camp from ill-treatment in a situation where their captors possessed locally enough medical and food supplies to adequately care for them.

At the end of May another 530 prisoners were moved out with about 270 left behind, too incapacitated to move. Twenty-six days later 183 men reached Renau; it had indeed been a Death March. Of those left at the camp they all either died of illness or starvation or were killed by the guards.

Reading about the conditions under which these men lived and the hard work they were expected to do until they dropped is gut wrenching so I will move on to one bright note. Six men survived. Yes, out of 2,700 men Six survived. This is their story.

Gunner Owen Campbell, 2/10th Field Regiment

On the second Death March, Campbell and four others decided to use the first opportunity to escape. Out of sight of guards during an air attack, they slid down a 61-metre bank, hid in some bracken and rubbish, and lay quietly until the column had moved on. For four days they fought their way, sometimes on hands and knees, through the jungle in what they assumed was the general direction of the coast. The four other men all lost their lives but Campbell eventually spied a canoe. The canoeists, Lap and Galunting, took him to Kampong Muanad where Kulang, a local anti-Japanese guerrilla leader, was headman. The local people hid and cared for the sick man. Eventually, Kulang took Campbell down river to where an Australian SRD (Service Reconnaissance Department) unit was camped.

Bombardier Richard ‘Dick’ Braithwaite, 2/15th Australian Field Regiment.

During the early stages of the second march Dick Braithwaite was so ill with malaria that his mates had to hold him up at roll call. For him it was a question of escape or die. Taking advantage of a gap in the column, he slipped behind a fallen tree until everyone had gone by. Eventually he reached the Lubok River where an elderly local man called Abing helped him. Abing took Braithwaite in his canoe down river to his village, where he was looked after. Hidden under banana leaves, Braithwaite was paddled for 20 hours downstream to Liberan Island where he was rescued by an American PT boat and taken to nearby Tawi Tawi Island. A week later, after he had told his story, an Australian colonel came to see him in his hospital bed to tell him they were going in to rescue his friends:

I can remember this so vividly. I just rolled on my side in the bunk, faced the wall, and cried like a baby. And said ‘You’ll be too late’.

Private Keith Botterill, 2/19th Battalion,

Lance Bombardier William Moxham, 2/15th Australian Field Regiment,

Private Nelson Short, 2/18th Battalion

Botterill, Moxham, Short and another man, Gunner Andy Anderson, escaped from Ranau on 7 July and for some days hid in a cave on the slopes of Mount Kinabalu. They ran into a local man, Bariga, and had little option but to trust him with their story. Throughout the remainder of July, Bariga hid them and brought food. Anderson died of chronic dysentery and they buried him in the jungle. At this point, Bariga learnt that there was an Australian unit operating behind the lines in the area, and after the Japanese surrender on 15 August the three POWs were told to head out of the area and meet up with this unit. Nelson Short recalled as they lay exhausted in the jungle:

We said, ‘Hello, what’s this? Is this Japs coming to get us? They’ve taken us to the Japs or what?’ But sure enough it was our blokes. We look up and there are these big six footers. Z Force. Boy oh boy. All in greens.

Warrant Officer ‘Bill’ Sticpewich, Australian Army Service Corps;

The final escape from Ranau was that of Sticpewich and Private Herman Reither. Towards the end of July a friendly Japanese guard warned Sticpewich that all remaining POWs at Ranau would be killed. On the 28th he and Reither managed to slip out of the camp and hid in the jungle until the hunt for them died down. They moved on and were eventually taken in by a local Christian, Dihil bin Ambilid. Hearing of the presence of Allied soldiers, Dihil took a message to them from Sticpewich. Back came medicines and food but unfortunately Reither had already died from dysentery and malnutrition. There is a dark side to this story which you may wish to read in the following article by Lynette Silver.

These six survivors were alive to testify in court against their tormentors and to ensure that the world received eyewitness accounts of the crimes and atrocities committed at Sandakan, on the death marches and at Ranau. As a result of these trials, eight Japanese, including the Sandakan camp commandant, Captain Hoshijima Susumi, were hanged as war criminals. A further 55 were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment.

It is hard to explain the treatment of prisoners at Sandikan by their captors. The Imperial Japanese Army indoctrinated its soldiers to believe that surrender was dishonourable. POWs were therefore thought to be unworthy of respect. The IJA relied on physical punishment to discipline its own troops and allied prisoners formed the bottom rung of the military hierarchy. The fear of an uprising by the prisoners may have been behind the decision to make them weak through sickness and malnutrition. The fear of reprisal at the end of the war would have fuelled the decision to remove every trace of the 2,500 prisoners sent to Sandakan.